Intelligence and Ageing

One of the difficulties in talking about changes in intelligence as we age, is that intelligence is underpinned by a wide range of cognitive functions, and controlled by interrelated regions spread out across the brain. Individual differences can account for large variations in specific functions, and the different regions can adapt and compensate for each other.

Despite these differences, we do find that in general some cognitive abilities actually improve with age, while others decline.

Ageing in the Brain

The ageing process affects the brain at every level, from changes within individual cells like the deterioration of neuronal membranes or the shortening of axons, through to larger structural changes across the entire brain, like reduced cortical thickness and sub-cortical volumes.

These changes result in the average brain losing 2 grams of mass every year from around 26 onwards. By the time you reach 80, that adds up to almost 8% of your brain.

Age related changes to the brain occur first in the prefrontal cortex. This is the area at the front of the brain associated with memory, emotion, and executive function. It is also the area associated with dementia and most neurodegenerative disorders.

When viewed as single traits both fluid and crystalized intelligence show a peak at age 26, followed by a steady decline. Although it is worth noting that crystalized intelligence decreases at a much slower rate.

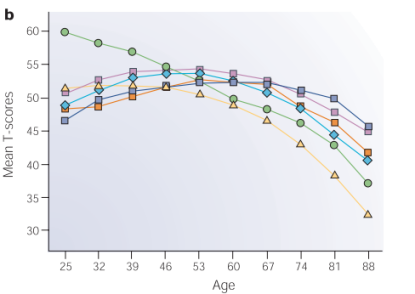

Even if you’ve passed the magic number of 26, it isn’t quite time to accept it’s all downhill from here. The real story only appears when we break apart the generalised traits of fluid and crystalized intelligence and take a look at more specific cognitive abilities, like the 2004 study; Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience.

You can see that Perceptual Speed is the first ability to peak, at only 25, after that it’s quite a wait, with every other trait still rising until Numeric Ability reaches a maximum at age 39. Although it ultimately drops furthest of all abilities, there decline is only very slight until after 60.

The remaining four abilities; Verbal Memory, Inductive Reasoning, Spatial Reasoning and Verbal Ability, all follow a similar pattern. They flatten out to a gentle peak somewhere between mid-fifties and early sixties before going into a slow decline.

A couple more points to notice, Verbal Ability is at the same level approaching ninety as it was at twenty five. Inductive Reasoning isn’t far behind, only dropping by a few points over 60 years.

This data largely matches up with what we experience in everyday life, as people age they tend to lose some of their sharpness in adapting to new situations, and some speed in problem solving, but keep hold of existing skills and knowledge for much longer.

However there are two questions which really stand out; firstly why are Verbal Ability and Inductive Reasoning so resistant to age-related decline? And secondly, if the average peak of individual cognitive traits seems to be somewhere around the early fifties, why do other studies suggest the more all-encompassing ideas of Fluid and Crystalized Intelligence peak at only twenty five?

Simply put, we continue to use these skills more than the others. It is easy for our Numerical Reasoning to slip, unless we make a conscious effort to keep it in good shape, but it is virtually impossible not to use our Verbal Ability or Inductive Reasoning skills on a daily basis.

Ultimately it all comes back to the principles of increasing intelligence; novelty and difficulty. While there are always exceptions to the rule, it is common for people to find themselves in less challenging and constantly changing environmental conditions as they get older. As a result many areas of the brain have to work less hard, and so are the first to deteriorate due to less use. Is it really a coincidence that many of the traits drop suddenly after sixty when people who experience a cognitive advantage due to a complex or demanding career, quickly lose those benefits after retirement.

Particularly in western cultures, as people move into old age they are more likely to find themselves isolated, with smaller and less dynamic social circles. We evolved primarily as a social species, with our larger brains needing to keep track of complex internal group relationships. As this demand is taken away, our brains relax and so use less of their cognitive resources.

Study after study show that people who are socially, mentally and physically active, consistently perform better across the board on cognitive tests than their peers who are less stimulated.

Chaning the Rate of Decline

One thing it is vital to remember when looking at statistical results from any sociological scientific research papers like these, is what you are seeing is averages. Individual differences count for a huge amount .

Clear links exist between the speed of cognitive decline and a wide range of factors. Fortunately, the vast majority of these factors are within our ability to control. Changes to lifestyle, nutrition and cognitive training, have all been shown to either slow the rate of deterioration or in some cases actually reverse age-related cognitive decline.

Neuroplasticity is a key component of all cognitive changes. Whenever we practice an activity, electrochemical signals are transmitted through the brain in a specific pattern over and over again. This repetition strengthens the connections between neurons in the specific pattern required to complete the activity, leading to a more efficient transmission of these signals.

Making the most of any cognitive training, is all about identifying ‘domain wide improvements’. These are the skills, exercises or games which do not only increase the ability to perform the specific exercise being practiced, but deliver transferrable improvements which benefit other tasks as well. Playing chess for example, can improve abilities in a wide range of other activities that involve weighing up multiple alternatives, strategic thinking and forward planning.

The more demanding cognitive exercises you engage in, the more you encourage the brain to establish new neural networks, connecting different regions of the brain. This is known as developing cognitive reserve.

In the event of damage or deterioration in some area of the brain, whether due to age related decline or a medical condition, these alternative networks can be used to bypass the damaged area without a significant loss of cognitive abilities. The level of cognitive reserve is one of the major indicators of overall cognitive function, particularly amongst older people.

Research published in ‘Trends in Cognitive Sciences’ shows that what you do in old age is far more important than what you did earlier in life when it comes to maintaining a youthful brain. So it just goes to show it is never too late to learn a new skill, and the decreases in cognitive function we associate with old age are much more about the expectations and standards we set for ourselves than they are about biological limits.

References

Finch CE. The neurobiology of middle-age has arrived. Neurobiology of Aging.2009 Apr;30(4):515-20;

Hedden T, Gabrieli JD. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004 Feb;5 (2):87-96.

Lars Nyberg, Martin Lövdén, Katrine Riklund, Ulman Lindenberger, Lars Bäckman. Memory aging and brain maintenance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2012; 16 (5): 292

Rushton JP, Ankney CD. Whole brain size and general mental ability: a review, International Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;119 (5):691-731

Theresa M. Harrison, Sandra Weintraub, M.-Marsel Mesulam and Emily Rogalski. Superior Memory and Higher Cortical Volumes in Unusually Successful Cognitive Aging, Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 2012